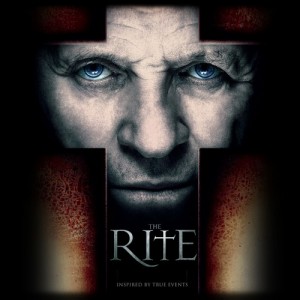

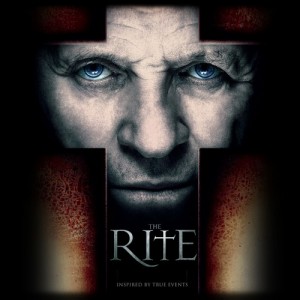

The new movie, The Rite, #1 at the North American box office this past weekend, once again reveals Hollywood’s fascination with exorcism. 1973’s The Exorcist began this trend in earnest, with 2005’s The Exorcism of Emily Rose a more recent example. All three movies are at least in part based on actual cases.

The new movie, The Rite, #1 at the North American box office this past weekend, once again reveals Hollywood’s fascination with exorcism. 1973’s The Exorcist began this trend in earnest, with 2005’s The Exorcism of Emily Rose a more recent example. All three movies are at least in part based on actual cases.

Whenever a movie like this appears on the scene, interest in real-life exorcisms begins to spike. It is therefore necessary to ask, “Did Jesus himself perform exorcisms?”

It may surprise some readers of the Gospels to learn that there were many exorcists who abounded in Jesus’ day. The Lord himself acknowledged this when he asked the Pharisees, “by whom do your sons cast them (demons) out?” (Matthew 12:27). According to the Jewish historian Josephus, exorcists needed: 1) A formula from Solomon to be incanted, along with 2) A piece of wood (called “bunk” or “the bunk stick”), which had a scent from the Barras root (see Josephus, JW 7.6.3; Ant. 8.2.5, 46-49).

The exorcist would use the bunk stick to draw the demon out of the nose (the ancients believed spirits would enter/exit a person via the nostrils). Heck, the person would probably sneeze (due to the scent of the Barras root), and the exorcist would say, “Look, there goes the demon!” Hmm…I wonder if that’s why people say, “God bless you” when someone sneezes!

On a more serious note, the reason why Jewish exorcists used incantations from Solomon was because, as Dr. Craig A. Evans points out in his magisterial commentary on Mark, “The tradition of Solomon as exorcist par excellence was widespread in late antiquity. The tradition began in 1 Kings 4:29-34 and was enhanced in later traditions such as Wisdom 7:17-21 and the Testament of Solomon. As ‘son of David’ (Mark 10:47, 48), Jesus would have been expected in some circles to effect cures paralleling those effected by David’s famous son Solomon” (Evans, Mark 8:27-16:20, Word Biblical Commentary, vol. 34b, p. 49).

Jesus was, in fact, well known as an exorcist. The Gospels are littered with references to this, and no serious scholar of the matter doubts it. But what made Jesus’ exorcisms much more impressive than that of others in his time was the manner by which Jesus performed them. He had no need of rigmarole, incantations, the Barras root, or any other “bunk’, if you’ll pardon the pun. He simply says to the demons, in effect, “Shut up, and get out!”

And they went into Capernaum; and immediately on the Sabbath he entered the synagogue and taught. And they were astonished at his teaching, for he taught them as one who had authority, and not as the scribes. And immediately there was in their synagogue a man with an unclean spirit; and he cried out, “What have you to do with us, Jesus of Nazareth? Have you come to destroy us? I know who you are, the Holy One of God.” But Jesus rebuked him, saying, “Be silent, and come out of him!” And the unclean spirit, convulsing him and crying with a loud voice, came out of him. And they were all amazed, so that they questioned among themselves, saying, “What is this? A new teaching! With authority he commands even the unclean spirits, and they obey him.” And at once his fame spread everywhere throughout all the surrounding region of Galilee (Mark 1:21-28).

Many wonder why Jesus would command silence from the demon, considering it correctly identified Jesus as “the Holy One of God”. Part of the answer lies in the fact that as the Messiah, Jesus did not want acclamation from demons – that is, he doesn’t want to use them as his P.R. team! Also, given the tense political situation of the time and the possible danger to Jesus’ life that a premature public announcement of his messiahship could bring (other, false messianic claimants of the day were executed as political threats to Rome), silence was prudent for the moment. As seen in the exorcism films, exorcisms also involve a power struggle around the issue of names. Knowing someone’s name implies having some sort of power over them. Hence, the exorcist attempts to get the demon to give up its name. This is also why the demon in the aforementioned incident was attempting to make known Jesus’ true identity. Of course, Jesus silences the evil spirit, but it is always fascinating to note that, while demons do recognize Jesus’ true identity and must obey him, human beings often do not.

Should we be worried about the presence of the demonic in our own day? As C.S. Lewis once put it, in The Screwtape Letters, there are two errors we can fall into, like ditches on either side of the road: “One is to disbelieve in their existence. The other is to believe, and to feel an excessive and unhealthy interest in them. They themselves are equally pleased with both errors”.

I’m not a huge poetry guy, but I’ve always been struck by this one: “Seven Stanzas at Easter”, by John Updike. I made use of it last night as I was giving a talk about the liturgical seasons of Lent and Easter. Updike’s poem emphasizes the bodily, corporeal reality of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. This was a real, historical event, not a metaphor. Christ really rose physically from death, leaving an empty tomb behind. As Saint Paul stresses, “If Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is vain, and and your faith is in vain” (1 Corinthians 15:14). Or, as Updike puts it:

I’m not a huge poetry guy, but I’ve always been struck by this one: “Seven Stanzas at Easter”, by John Updike. I made use of it last night as I was giving a talk about the liturgical seasons of Lent and Easter. Updike’s poem emphasizes the bodily, corporeal reality of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. This was a real, historical event, not a metaphor. Christ really rose physically from death, leaving an empty tomb behind. As Saint Paul stresses, “If Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is vain, and and your faith is in vain” (1 Corinthians 15:14). Or, as Updike puts it:

The new movie, The Rite, #1 at the North American box office this past weekend, once again reveals Hollywood’s fascination with exorcism. 1973’s The Exorcist began this trend in earnest, with 2005’s The Exorcism of Emily Rose a more recent example. All three movies are at least in part based on actual cases.

The new movie, The Rite, #1 at the North American box office this past weekend, once again reveals Hollywood’s fascination with exorcism. 1973’s The Exorcist began this trend in earnest, with 2005’s The Exorcism of Emily Rose a more recent example. All three movies are at least in part based on actual cases.