Today’s first reading from 1 Corinthians 15 contains one of the first “creeds” of the early Church. As Saint Paul writes,

Today’s first reading from 1 Corinthians 15 contains one of the first “creeds” of the early Church. As Saint Paul writes,

“For I handed on to you as of first importance what I also received:

that Christ died for our sins

in accordance with the Scriptures;

that he was buried;

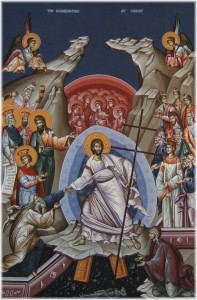

that he was raised on the third day

in accordance with the Scriptures;

that he appeared to Cephas, then to the Twelve.

After that, he appeared to more

than five hundred brothers at once,

most of whom are still living,

though some have fallen asleep.

After that he appeared to James,

then to all the Apostles.

Last of all, as to one born abnormally,

he appeared to me.”

– 1 Corinthians 15:3-8

In an interview with Lee Strobel for the book The Case for Christ, scholar Gary Habermas showed that Saint Paul is, in fact, quoting a very early creed of the Church. First, Paul uses the terms translated “received” and “handed on”, technical rabbinical language for the passing on of sacred tradition. The text is also in stylized format, using parallelism, presumably to aid memorization. The use of the Aramaic version of Peter’s name, “Cephas” is likely a sign of its primitive date. The creed also uses phrases that are uncommon in Paul’s writings: “the Twelve”; “he was raised”; “the third day”. Habermas noted that scholar “Ulrich Wilkens says that it ‘indubitably goes back to the oldest phase of all in the history of primitive Christianity'” (Strobel, The Case for Christ, p. 230).

Habermas, among others, would contend that this creed could have been composed within mere months after the resurrection of Jesus. He notes that no credible scholar disputes Pauline authorship of 1 Corinthians, which was likely written between 55-57 AD. But Paul says in 15:3 that he passed the creed on to the Corinthian Church at some point in the past, predating his visit there in 51 AD. That places the composition of the creed no later than within 20 years of the original Easter event.

But Habermas – and others – think the creed goes back even further: between 32-38 AD, when Paul received it, in all likelihood in Jerusalem. Three years after Paul’s conversion, he travelled to Jerusalem to interview the Apostles Peter and James (whose feast day we celebrate today). Habermas draws our attention to the fact that, when Paul described this trip in Galatians 1:18-19, he uses the Greek word historeo, which indicates a thorough investigation of the facts surrounding Jesus’ resurrection was being made. So, in all likelihood, this creed was delivered to Paul by the eyewitnesses of the resurrected Jesus, Peter and James.

Of course, the creed goes on to enumerate other Easter eyewitnesses, including an appearance of the Risen Christ to over 500 people at once – “most of whom are still living” at the time Paul wrote 1 Corinthians. Paul is virtually daring any skeptics to interview these people.

The 1 Corinthians creed authenticates the resurrection of Christ in many ways, not the least of which is this: its incredibly early, eyewitness testimony precludes any possibility of legendary accretion. The fact is, the resurrection is a fact.