Bishop Robert Barron, Auxiliary Bishop of Los Angeles and founder of Word on Fire ministries, has offered up yet another great movie review. This one’s on director Martin Scorsese’s Silence, long in the making, which adapts Shusaku Endo’s 1966 novel of the same name. It deals with (spolier alert) the apostasy of certain Jesuit missionaries in Japan during that nation’s bloody persecution of Catholics in the 17th century. Barron refutes the idea that the choice these men made should be lauded:

Bishop Robert Barron, Auxiliary Bishop of Los Angeles and founder of Word on Fire ministries, has offered up yet another great movie review. This one’s on director Martin Scorsese’s Silence, long in the making, which adapts Shusaku Endo’s 1966 novel of the same name. It deals with (spolier alert) the apostasy of certain Jesuit missionaries in Japan during that nation’s bloody persecution of Catholics in the 17th century. Barron refutes the idea that the choice these men made should be lauded:

What in the world do we make of this strange and disturbing story? Like any great film or novel, Silence obviously resists a univocal or one-sided interpretation. In fact, almost all of the commentaries that I have read, especially from religious people, emphasize how Silence beautifully brings forward the complex, layered, ambiguous nature of faith. Fully acknowledging the profound psychological and spiritual truth of that claim, I wonder whether I might add a somewhat dissenting voice to the conversation? I would like to propose a comparison, altogether warranted by the instincts of a one-time soldier named Ignatius of Loyola, who founded the Jesuit order to which all the Silence missionaries belonged. Suppose a small team of highly-trained American special ops was smuggled behind enemy lines for a dangerous mission. Suppose furthermore that they were aided by loyal civilians on the ground, who were eventually captured and proved willing to die rather than betray the mission. Suppose finally that the troops themselves were eventually detained and, under torture, renounced their loyalty to the United States, joined their opponents and lived comfortable lives under the aegis of their former enemies. Would anyone be eager to celebrate the layered complexity and rich ambiguity of their patriotism? Wouldn’t we see them rather straightforwardly as cowards and traitors?

Indeed, the true heroes of the film are the Japanese lay martyrs, not the apostate Jesuits. And, as Barron notes, there are more than a few similarities between how cultural elites in 17th-century Japan and those of today want to “silence” (sorry, couldn’t resist) the faith today:

My worry is that all of the stress on complexity and multivalence and ambiguity is in service of the cultural elite today, which is not that different from the Japanese cultural elite depicted in the film. What I mean is that the secular establishment always prefers Christians who are vacillating, unsure, divided, and altogether eager to privatize their religion. And it is all too willing to dismiss passionately religious people as dangerous, violent, and let’s face it, not that bright.

The whole review, as is the case with anything by Bishop Barron, is well worth your time and can be found here.

Q. We’ve seen a spate of biblically themed movies in theatres lately: Son of God, Noah (starring Russell Crowe), and now Exodus: Gods and Kings (featuring Christian Bale of Batman fame). Why do you think this is?

Q. We’ve seen a spate of biblically themed movies in theatres lately: Son of God, Noah (starring Russell Crowe), and now Exodus: Gods and Kings (featuring Christian Bale of Batman fame). Why do you think this is? Q. The movie Noah, starring Russell Crowe, has inspired me to look into the biblical Noah. What does the Bible say about Noah and the Flood in Genesis 6:5-8:22?

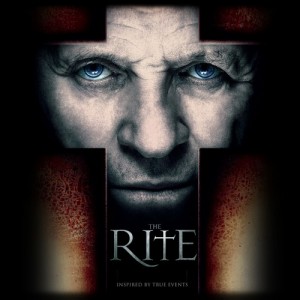

Q. The movie Noah, starring Russell Crowe, has inspired me to look into the biblical Noah. What does the Bible say about Noah and the Flood in Genesis 6:5-8:22? The new movie, The Rite, #1 at the North American box office this past weekend, once again reveals Hollywood’s fascination with exorcism. 1973’s The Exorcist began this trend in earnest, with 2005’s The Exorcism of Emily Rose a more recent example. All three movies are at least in part based on actual cases.

The new movie, The Rite, #1 at the North American box office this past weekend, once again reveals Hollywood’s fascination with exorcism. 1973’s The Exorcist began this trend in earnest, with 2005’s The Exorcism of Emily Rose a more recent example. All three movies are at least in part based on actual cases.