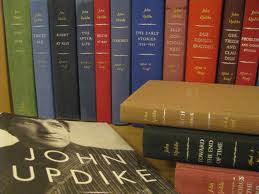

I’m not a huge poetry guy, but I’ve always been struck by this one: “Seven Stanzas at Easter”, by John Updike. I made use of it last night as I was giving a talk about the liturgical seasons of Lent and Easter. Updike’s poem emphasizes the bodily, corporeal reality of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. This was a real, historical event, not a metaphor. Christ really rose physically from death, leaving an empty tomb behind. As Saint Paul stresses, “If Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is vain, and and your faith is in vain” (1 Corinthians 15:14). Or, as Updike puts it:

I’m not a huge poetry guy, but I’ve always been struck by this one: “Seven Stanzas at Easter”, by John Updike. I made use of it last night as I was giving a talk about the liturgical seasons of Lent and Easter. Updike’s poem emphasizes the bodily, corporeal reality of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. This was a real, historical event, not a metaphor. Christ really rose physically from death, leaving an empty tomb behind. As Saint Paul stresses, “If Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is vain, and and your faith is in vain” (1 Corinthians 15:14). Or, as Updike puts it:

Make no mistake: if He rose at all it was as His body; if the cells’ dissolution did not reverse, the molecules reknit, the amino acids rekindle, the Church will fall.

It was not as the flowers, each soft Spring recurrent; it was not as His Spirit in the mouths and fuddled eyes of the eleven apostles; it was as His flesh: ours.

The same hinged thumbs and toes, the same valved heart that–pierced–died, withered, paused, and then regathered out of enduring Might new strength to enclose.

Let us not mock God with metaphor, analogy, sidestepping, transcendence; making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the faded credulity of earlier ages: let us walk through the door.

The stone is rolled back, not papier-mâché, not a stone in a story, but the vast rock of materiality that in the slow grinding of time will eclipse for each of us the wide light of day.

And if we will have an angel at the tomb, make it a real angel, weighty with Max Planck’s quanta, vivid with hair, opaque in the dawn light, robed in real linen spun on a definite loom.

Let us not seek to make it less monstrous, for our own convenience, our own sense of beauty, lest, awakened in one unthinkable hour, we are embarrassed by the miracle, and crushed by remonstrance.