(My article in Catholic Insight‘s December issue.)

(My article in Catholic Insight‘s December issue.)

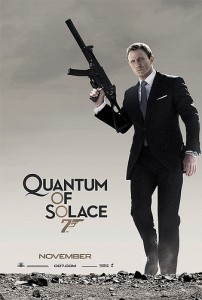

James Bond is film’s most enduring character. Now in his 22nd official movie, agent 007’s latest celluloid adventure is called Quantum of Solace. The title is borrowed from a heretofore little-known Bond short story by creator Ian Fleming.

It’s a double entendre: “Quantum” is the nefarious terrorist organization Bond battles in the film. A quantum is also defined as “a share or portion”. Bond is searching for his piece of peace, his own “quantum of solace”, following the events of the last installment, the superior Casino Royale (2006).

Quantum of Solace is an incredibly stylish film, and moves along at a much quicker pace than its predecessor – in fact, it’s the shortest Bond film in history, whereas Casino Royale, directed by Martin Campbell, was the longest. The added time did allow for proper character development. But Quantum‘s director, Marc Forster, had a different vision for his film – he wanted it to be faster – in his words, “like a bullet”.

Royale was a reboot of the series, where we discovered, along with new Bond actor Daniel Craig, how Bond becomes Bond, the British Secret Service agent with the license to kill. He also falls in love with the beauteous Vesper Lynd, who, forced to betray him and overwhelmed by guilt, commits suicide. Quantum picks up the storyline as Bond seeks revenge on those responsible.

At one point in Royale, Bond says to Vesper, “Do what I do for long enough, and there won’t be any soul left to save”. For love of her, he actually resigns from Her Majesty’s Secret Service until Vesper’s death. In Quantum, Bond gets back to the business of spying – and losing his soul – with a vengeance. This occurs in four ways:

Bond is saturated with sex, but never finds True Love. After losing Vesper, Bond (perhaps brokenhearted) reverts to his old, philandering ways in Quantum with fetching fellow agent Strawberry Fields. Her name – and “crude” fate – recalls Bond girls of the ‘60s, one of several nods to early 007 films. Vesper once chided him, “You think of women as disposable pleasures”. Clearly, Bond has not read Humanae Vitae, also from the ‘60s. He has yet to overcome lust, or discover that the self-gift of matrimonial sexual love points toward the Trinity itself – an eternal exchange of love. Only in light of the God who is Love will Bond discover the love he truly desires.

Bond is immersed in intelligence, but never knows Truth. Ethical dilemmas abound in Quantum. The CIA is in bed, so to speak, with the baddies, and so are the Brits. Bond’s boss/den mother, M (Judi Dench) is told by a British official that “If we only did business with good people, we’d have no one left to trade with”. Rene Mathis mentions to Bond that “When one is young, right and wrong are easy. When you’re older, it gets harder to tell”. Perhaps Pilate was thinking the same thing when deciding what to do with Jesus. When he asked Christ, “What is truth?” Truth itself was looking back at him. Today, like us, Bond has to battle more than dictators. He has to deal with what Pope Benedict called “the dictatorship of relativism”.

Bond is drawn to beauty, but never apprehends the Beautiful. From Tom Ford suits to Aston Martins, from exotic locales to fetching femme fatales, Bond has a taste for the finer things in life. But his keen powers of observation never notice what Fr. Thomas Dubay dubs “the evidential power of beauty” – that beautiful things point to the beautiful God who made them – and him.

Bond is merciless without finding Mercy. The ‘blunt instrument” of the last film is armed with razor-sharp, and lethal, hand-to-hand combat skills, courtesy of the stunt team from the Bourne trilogy. Regrettably, like those films, Quantum suffers from hard-to-follow quick cuts in the action, most of which involves Bond taking full advantage of his license to kill. But Bond, at a key moment, unexpectedly spares an adversary’s life. Why? To prove a point to M, or so he can sleep at night? Perhaps he heeded Mathis’ advice: “Vesper gave everything for you. Forgive her. Forgive yourself”. Has 007 learned mercy? We shall see. But we must learn it – from our divine teacher, Christ, who truly gave everything for us, so we could forgive and be forgiven. As a fictional character, Bond can’t really discover this. Only we can experience Jesus, the Prince of Peace, our true Quantum of Solace.

I was invited to speak at the Humanae Vitae: A Buried Treasure Conference held at the University of Toronto on Saturday, November 15. Despite the dreary weather, approximately 400 people jammed into the Sam Sorbara Auditorium, with over 200 people being turned away, either at the door or by phone, who were looking for tickets! I can’t lie – they certainly weren’t there to see me!

I was invited to speak at the Humanae Vitae: A Buried Treasure Conference held at the University of Toronto on Saturday, November 15. Despite the dreary weather, approximately 400 people jammed into the Sam Sorbara Auditorium, with over 200 people being turned away, either at the door or by phone, who were looking for tickets! I can’t lie – they certainly weren’t there to see me!  (Here’s my latest article, from Catholic Insight magazine’s November issue.)

(Here’s my latest article, from Catholic Insight magazine’s November issue.) I recently came across a very interesting blog by Lee Thomas Dahn. It’s called

I recently came across a very interesting blog by Lee Thomas Dahn. It’s called